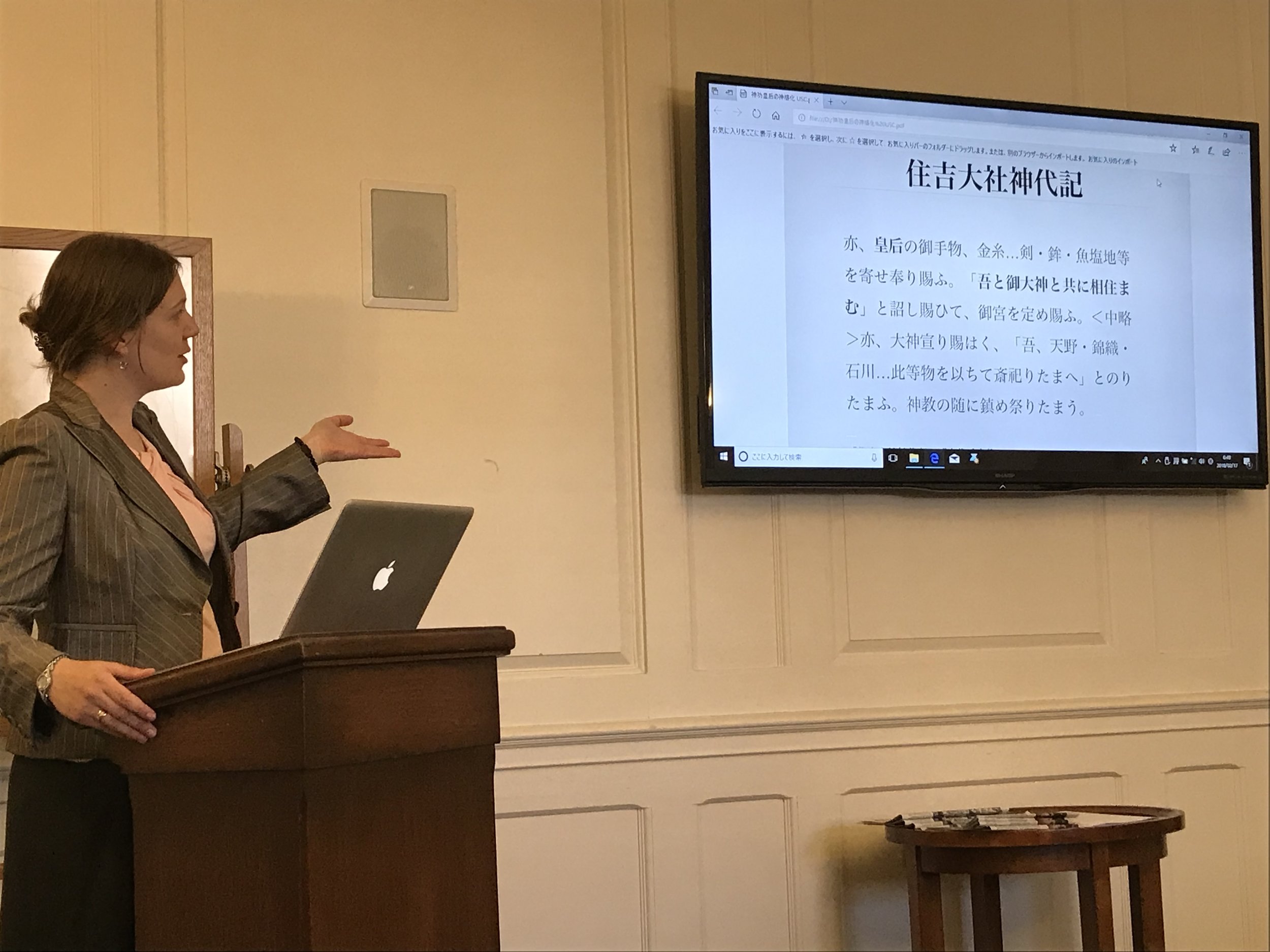

In his Taiki journal, covering the years from 1136 to 1155, the late Heian courtier and intellectual Fujiwara no Yorinaga (1120-1156) discussed many aspects of his personal studies. A very athletic child, he suffered a riding accident at the age of seventeen and turned his interests towards books. Studying under several private tutors, Yorinaga focused on reading Chinese classics, history, and law. Although the chosen texts themselves were not odd choices for a Heian courtier, the amount of time Yorinaga spent reading and studying went beyond what was expected in the Royal University, and beyond what many scholars read themselves. His method of self-study marked a turning point in the methods of education for elites, since he was the last major scholar of the Heian period. Of special importance is the entry for 1143.9.29 in his courtier. It contains lists and notes of 1,030 volumes of texts he had read up to that point. My presentation today concerns this entry. I will discuss the contents of Yorinaga’s reading list, focusing on what and why Yorinaga may have chosen particular titles for study, how the reading list compares to the curriculum set out in the much earlier Daigaku-ryô, and issues of translation.

藤原頼長が読んだ本を中心に「台記」康治2年9月29日

藤原頼長の「台記」という日記の中で、自分の勉強や教育についていっぱい書いています。子供の時、スポーツ万能ですが、十七歳の時、馬乗り間に事件があって、その後に本や勉強に興味が変わりました。家庭教師を使って、経書や経史や法学を勉強始めました。平安時代の公家について、変な本ではありませんが、読む時間はすごく長いんで、大学院生に比べて長いでした。自習の方法は平安時代の節目で、頼長は平安時代の最後の主要な学者でした。特に「台記」康治2年(1143年)9月29日に、頼長が読んだ1030巻の本が記録しています。この発表で、頼長が読んだ本のリストを見つめ直すつもりです。特に、なぜその本を選んだか、大学寮に入った本に比べるか、翻訳の問題について話したいんです。